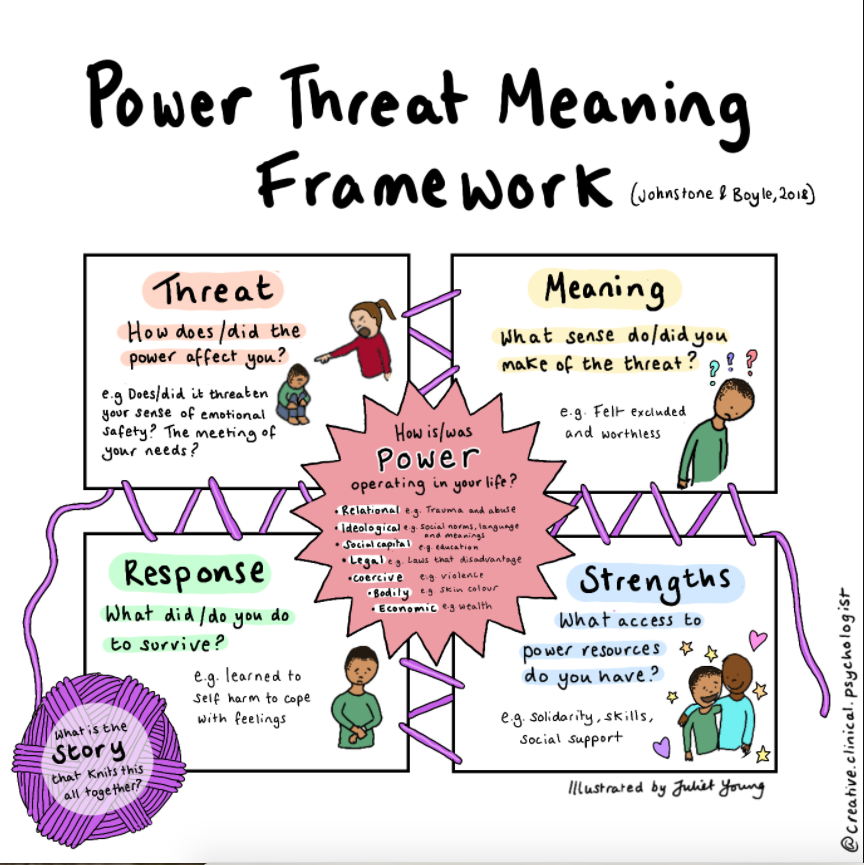

Over the years, I have often heard people describe how they ‘have depression’, or ‘have anxiety’. Sometimes people have spoken about the ‘illness’ they have been described as having; some kind of personality disorder, or a newly-identified variant of post-traumatic stress disorder. Sometimes a new doctor will diagnose a new illness. Some people have lived with their ‘illness’ for many years and have come to the conclusion that it is something incurable; it must simply be endured much like a chronic physical condition such as diabetes. Medication may help to change how they are feeling and this can be a significant relief. The medication, they are often told, puts right (for the short or the long term) a ‘chemical imbalance’ in their brain, and whilst this may be helpful it is rarely asked exactly what this imbalance is and why it should exist in the first place. It’s just one of those things; why does anyone get any illness? Sometimes, having their ‘illness’ named and responded to by a doctor can come as a great relief; finally their distress is being recognised and validated. They have a recognised illness and are not ‘just making things up’ or are not ‘not trying hard enough’. Having a medically diagnosed illness can seem like - and often is - the only way to have human distress recognised, taken seriously, and helpfully responded to. In my initial training I learned that the word ‘psychotherapy’ has its roots in the Greek words ‘Psyche’ (meaning 'breath’, spirit, or ‘soul') and therapeia (meaning healing). This implies that how we approach non-physical maladies is distinct from our approach to healing physical illness, or illnesses of the body (or ‘soma’ in the Greek). Also, that ‘psychotherapy’ is about the healing of souls and that ‘psychotherapists’ are soul-healers. It would be interesting to discover how many mental health practitioners would be comfortable thinking of themselves in this way? Talk of ‘soul’ does not fit comfortably with modern mainstream approaches to supporting distressed people. Western medicine has long prioritised what can be objectively seen and measured. This is one of its great strengths; it is not hard to make a long list of its achievements and it would be hard to argue that it has not brought immense benefits to humanity. It is difficult to imagine the world without the knowledge we now have about the human body and how to care for it, even if we do not always arrange our political structures in ways that share the fruits of this knowledge equitably. It is harder to claim that western medicine has managed to understand and respond to non-physical distress. Adopting a rationalist, reductionist paradigm, the disciplines of psychiatry and psychology have tended to treat the physical and non-physical in the same way; seeing both as subject to evident, predictable rules. It is as though, knowing the success of this approach with physical ailments, non-physical experiences (such as feeling overwhelmingly sad, or ashamed, or frightened) have been shoe-horned into the same mould, even though many practitioners know full well that they do not fit. This medical model of how to approach difficulties is so entrenched in how we organise our society, that many mental health practitioners go along with it because it is the ‘only show in town’. As a person-centred therapist, I can recognise and respond to the uniqueness of the person in front of me who is telling their individual story. This luxury is not available to the person making decisions about how best to spend public funds. To do this well, they need to respond to what a population needs and in order to do so, they need reliable facts and figures about groups and trends within that population. Knowing how best to establish good services for distressed people, therefore, demands a way of grouping people together according to what kind of distress they are experiencing. At the moment, the diagnosis of psychiatric conditions is the only available option for doing this. It affects how health and social care services are planned and delivered as well as controlling access to state benefits. This puts the medical model in a conflicted position because psychiatry and those working in psychiatric systems are required to be agents of society, whilst simultaneously purporting to be supporting the individual. To the extent that it offers a commonly understood structure, this approach built upon the medical model is to be respected. However, it is increasingly clear that other structures may provide a more accurate way of recognising common patterns in human distress, recognise the uniqueness of each person’s experience, and at the same time avoid the mistake of trying to impose a physical understanding on non-physical experiences. A number of organisations (often initiated by service-users) such as A Disorder for Everyone have been active in questioning this pervasive understanding of non-physical distress, but recently the British Psychological Society have published the Power Threat Meaning Framework, (PTMF) as an alternative to trying to diagnose problematic human experiences as though they are medical conditions to be diagnosed by a medically qualified person. This is a huge document, and even the summary version is substantial! An accessible account of it has been produced in a book by Mary Boyle and Lucy Johnstone, two clinical psychologists who have been closely involved with its development The PTMF attempts to change the discourse around distress from ‘What is wrong with me?’ to ‘What has happened to me?’ It does not deny that physical conditions affect our psychological functioning. I know this truth from personal experience. Some years ago I sustained a brain injury. After the initial stages of recovery, I was greatly helped when it was explained to me by a neurologist that some of my responses, which a doctor might be inclined to see and treat as ‘depression’ were, in fact, a result of the very specific nature of where my brain tissue had sustained damage. For me to have been prescribed antidepressant medication might (or might not) have modified my experience, but it would not have changed the fact of my injured brain. So, although our brain chemistry is affected by our experience, and vice versa, the British psychiatrist, Joanna Moncrieff argues persuasively that the explanation often given to patients that distressing experiences are caused by a ‘chemical imbalance’ in the brain is one that has never had the support of credible scientific evidence. Medication indisputably affects how we feel and can be very helpful, but to claim that it can ‘cure’ mental illness is like claiming that hitting the television set to improve the picture deals with the electrical problem. The central problem with using a medical model as a response to non-physical distress is that it must identify what is wrong, in order to cure it. Therefore individuals must be assigned to a group based on diagnosis and given treatment to cure what is pathological in this particular diagnosis. In many countries, it is impossible to access support without a medical diagnosis to say precisely what is wrong. But what if nothing is wrong with me? What if my experience is an entirely understandable and normal reaction to what has happened to me? The PTMF is an attempt to develop a new model of thinking about non-physical distress which can serve as a viable alternative to the long-established and deeply embedded paradigm of the medical model. This is no small task. In scale, it is perhaps not unlike the current Herculean struggle to leave behind a carbon-based economy that has shaped the modern world. It suggests that power, and how it is used or misused, has significant effects on our life from our birth. Power can be legal, economic, interpersonal, biological, coercive, social/cultural, or ideological. It relates to our relationships, our emotional life, our education, our employment. It relates to our thoughts and feelings as well as to our physical embodiment. It seems self-evident that we live in a world where power is not held equally. For individuals the PTMF asks these questions: 1. What has happened to you? 2. How did it affect you? 3. What sense did you make of it? 4. What did you have to do to survive it? These are questions we can all ask ourselves. For those who are distressed, these questions can open the possibility that they are not ill, but that their life has required them to find ways of surviving very difficult experiences. Drawing on an increased understanding of how humans respond to threatening experiences, the PTMF suggests that responses to adverse experiences - in childhood and as adults - are based on our need to regulate difficult feelings, and to give us protection against loss, hurt, or abandonment. Thus it is possible to move to the idea that a person’s response is not pathological, but a normal response to an abnormal experience. This will not be a new idea to many people who work to support individuals in their response to difficult life experiences. Unfortunately, on its own it is not an idea that can be used at a public policy level. The PTMF is new and bold in its attempt to provide a new way of classifying distress. This classification is needed by politicians and planners, even if individual therapists may baulk at the idea of grouping people together. It attempts to address the paradox of how we are both unique and also like other people. Neither side of the paradox is helpful on its own. The crucial step away from diagnostic categories however is that patterns of experience are organised by meaning and not on biologically-based medical models. The patterns may include biological factors (as my brain injury experiences do), but they are not defined by them. The general patterns provisionally suggested in the PTMF are verbs not nouns. They are experiences not biological facts. They are not a replacement for diagnoses, in fact they cut across traditional diagnoses, psychiatric specialisms, ideas of what is healthy and what is pathological. They aim to assure individuals that they are not ‘abnormal’, that their experiences make sense, and that theirs is a normal way of reacting rather than an illness, even if it may have been distressing and cost them dearly. The aim is not to diminish individuality, but points to the helpfulness of Carl Roger’s comment that what is most personal is also most universal. The current - provisional - list of patterns has seven groupings of experiences: 1. Questions of personal identity. 2. Surviving rejection, entrapment, and invalidation as a person. 3. Surviving insecure attachments as a child or young person. 4. Surviving separations and/or identity confusion. 5. Surviving defeat, entrapment, disconnection, or loss. 6. Surviving social exclusion, shame, or coercive relationships. 7. Surviving single threats. These general patterns can offer an overarching structure for identifying patterns of emotional distress, unusual experiences, and troubling behaviour and are offered as an alternative to medical diagnostic categories based on poorly evidenced biological claims. The ongoing development of the PTMF gives me encouragement that my way of working is not invalidated simply by sitting outside the mainstream medical model of human distress. Indeed, it is part of a wider movement (including people working uncomfortably within the mainstream) towards a more human way of responding as a society to our fellow human beings. It is a way which does not seek to find out what is wrong with an individual, but which wants to hear their story in order to validate them as having responded as best they could to difficult things. This then opens up possibilities of finding new and perhaps more rewarding responses. It also moves the spotlight away from only highlighting the individual and asks uncomfortable and challenging questions of our society and political systems in which power and resources are so unevenly distributed.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Occasional writing not published elsewhere.ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed